Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

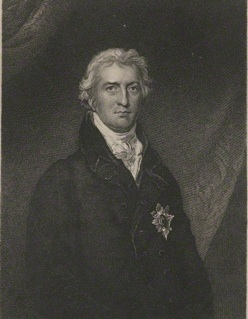

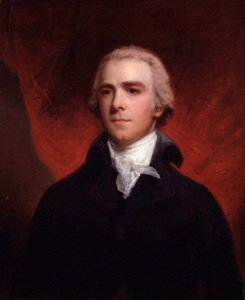

George Canning

11 April 1771 – 8 August 1827

George Canning

A British statesman and politician who served as Foreign Secretary and briefly Prime Minister. He is remembered for the shortest service as Prime Minister, dying of pneumonia in office just a little after serving for four months. He is also known for the duel that he engaged in and lost to Lord Castlereagh in 1809.

Early life: 1770–1793

Canning was born into an Anglo-Irish family at his parents’ home in Queen Anne Street, Marylebone, London. Canning described himself as “an Irishman born in London”. His father, George Canning, Sr., of Garvagh, County Londonderry, Ireland, was a gentleman of limited means, a failed wine merchant and lawyer, who renounced his right to inherit the family estate in exchange for payment of his substantial debts. George Sr. eventually abandoned the family and died in poverty on 11 April 1771, his son’s first birthday, in London. Canning’s mother, Mary Anne Costello, took work as a stage actress, a profession not considered respectable at the time.Indeed when in 1827 it looked as if Canning would become Prime Minister, Lord Grey remarked that “the son of an actress is, ipso facto, disqualified from becoming Prime Minister”.

Because Canning showed unusual intelligence and promise at an early age, family friends persuaded his uncle, London merchant Stratford Canning (father to the diplomat Stratford Canning), to become his nephew’s guardian. George Canning grew up with his cousins at the home of his uncle, who provided him with an income and an education. Stratford Canning’s financial support allowed the young Canning to study at Eton College and Christ Church, Oxford. Canning came out top of the school at Eton and left at the age of seventeen. His time at Eton has been described as “a triumph almost without parallel. He proved a brilliant classic, came top of the school, and excelled at public orations”.

Canning struck up friendships with the then-future Lord Liverpool as well as with Granville Leveson-Gower and John Hookham Frere. In 1789 he won a prize for his Latin poem The Pilgrimage to Mecca which he recited in Oxford Theatre. Canning began practising law after receiving his BA from Oxford in the summer of 1791, but he wished to enter politics.

Entry into politics: 1793–1795

Stratford Canning was a Whig and would introduce his nephew in the 1780s to prominent Whigs such as Charles James Fox, Edmund Burke, and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. George Canning’s friendship with Sheridan would last for the remainder of Sheridan’s life.

George Canning’s impoverished background and limited financial resources, however, made unlikely a bright political future in a Whig party whose political ranks were led mostly by members of the wealthy landed aristocracy in league with the newly rich industrialist classes. Regardless, along with Whigs such as Burke, Canning himself would become considerably more conservative in the early 1790s after witnessing the excessive radicalism of the French Revolution. “The political reaction which then followed swept the young man to the opposite extreme; and his vehemence for monarchy and the Tories gave point to a Whig sarcasm,—that men had often turned their coats, but this was the first time a boy had turned his jacket.”

So when Canning decided to enter politics he sought and received the patronage of the leader of the “Tory” group, William Pitt the Younger. In 1793, thanks to the help of Pitt, Canning became a Member of Parliament for Newtown on the Isle of Wight, a rotten borough. In 1796, he changed seats to a different rotten borough, Wendover in Buckinghamshire. He was elected to represent several constituencies during his parliamentary career.

Canning rose quickly in British politics as an effective orator and writer. His speeches in Parliament as well as his essays gave the followers of Pitt a rhetorical power they had previously lacked. Canning’s skills saw him gain leverage within the Pittite faction that allowed him influence over its policies along with repeated promotions in the Cabinet. Over time, Canning became a prominent public speaker as well, and was one of the first politicians to campaign heavily in the country.

As a result of his charisma and promise, Canning early on drew to himself a circle of supporters who would become known as the Canningites. Conversely though, Canning had a reputation as a divisive man who alienated many.

He was a dominant personality and often risked losing political allies for personal reasons. He once reduced Lord Liverpool to tears with a long satirical poem mocking Liverpool’s attachment to his time as a colonel in the militia. He then forced Liverpool to apologise for being upset.

Foreign Office: 1796–1799

On 2 November 1795, Canning received his first ministerial post: Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. In this post he proved a strong supporter of Pitt, often taking his side in disputes with the Foreign Secretary, Lord Grenville. At the end of 1798 Canning responded to a resolution by George Tierney MP for peace negotiations with France:

“I for my part still conceive it to be the paramount duty of a British member of parliament to consider what is good for Great Britain…I do not envy that man’s feelings, who can behold the sufferings of Switzerland, and who derives from that sight no idea of what is meant by the deliverance of Europe. I do not envy the feelings of that man, who can look without emotion at Italy – plundered, insulted, trampled upon, exhausted, covered with ridicule, and horror, and devastation – who can look at all this, and be at a loss to guess what is meant by the deliverance of Europe? As little do I envy the feelings of that man, who can view the peoples of the Netherlands driven into insurrection, and struggling for their freedom against the heavy hand of a merciless tyranny, without entertaining any suspicion of what may be the sense of the word deliverance. Does such a man contemplate Holland groaning under arbitrary oppressions and exactions? Does he turn his eyes to Spain trembling at the nod of a foreign master? And does the word deliverance still sound unintelligibly in his ear? Has he heard of the rescue and salvation of Naples, by the appearance and the triumphs of the British fleet? Does he know that the monarchy of Naples maintains its existence at the sword’s point? And is his understanding, and his heart, still impenetrable to the sense and meaning of the deliverance of Europe?”

Pitt called this speech “one of the best ever heard on any occasion”.

During his early period in the Foreign Office (1807–9) Canning became deeply involved in the affairs of Spain, Portugal and Latin America. He was responsible for a number of decisions that greatly affected the future course of Latin American history.

Great Britain had a strong interest in ensuring the demise of Spanish colonialism, and to open the newly-independent Latin American colonies to British trade. The Latin Americans received a certain amount of unofficial aid – arms and volunteers – from outside, but no outside official help at any stage from Britain or any other power. Britain also refused to aid Spain and opposed any outside intervention on behalf of Spain by other powers. Britain, and especially British sea power, was a decisive factor in the struggle for independence of certain Latin American countries.

In 1825 Mexico, Argentina and Colombia were recognised by means of the ratification of commercial treaties with Britain. In November 1825 the first minister from a Latin American state, Colombia, was officially received in London. “Spanish America is free,” Canning declared, “and if we do not mismanage our affairs she is English … the New World established and if we do not throw it away, ours.” Also in 1825, Portugal recognised Brazil (thanks to Canning’s efforts, and in return for a preferential commercial treaty), less than three years after Brazil’s declaration of independence.

On 12 December 1826, in the House of Commons, Canning was given an opportunity to defend the policies he had adopted towards France, Spain and Spanish America, and declared: “I resolved that if France had Spain it should not be Spain with the Indies. I called the New World into existence to redress the balance of the Old.”

Canning pushed through, against great opposition, British recognition of Argentina, Colombia, Mexico and Brazil. In a sense, therefore, he brought part of the New World into political existence. The United States had recognised these states earlier, but recognition by the leading world power was to be decisive. Recognition by Britain was greeted with enthusiasm throughout Latin America.

Canning, who was naturally and rightly more concerned with Britain’s political and economic interests in Latin America than with Latin American independence, did a great deal to enhance Britain’s prestige throughout Latin America. He was esteemed as a great liberal statesman who understood and sympathised with the cause of Latin American independence and who did more than any other foreign statesman to make it a reality. George Canning deserves credit as the first British Foreign Secretary to devote a large proportion of his time and energies to the affairs of Latin America (as well as to those of Spain and Portugal) and to foresee the important political and economic role the Latin American states would one day play in the world. It is appropriate that the home of the Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian Council in London should be called Canning House.

He resigned as Foreign Minister on 1 April 1799.

The Anti-Jacobin

Canning was involved in the founding of the Anti-Jacobin, a newspaper which was published on every Monday from 20 November 1797 to 9 July 1798. Its purpose was to support the government and condemn revolutionary doctrines through news and poetry, much of it written by Canning. Canning’s poetry satired and ridiculed Jacobin poetry. Before the appearance of the Anti-Jacobin all the eloquence (except for Burke’s) and all the wit and ridicule had been on the side of Fox and Sheridan. Canning and his friends changed this. A young Whig, William Lamb (the future Lord Melbourne, Prime Minister) wrote an ‘Epistle to the Editors of the Anti-Jacobin’, which attacked Canning:

Who e’er ye are, all hail! – whether the skill

Of youthful CANNING guides the ranc’rous quill;

With powers mechanic far above his age,

Adapts the paragraph and fills the page;

Measures the column, mends what e’er’s amiss,

Rejects THAT letter, and accepts of THIS;

Office: 1799–1800

In 1799 Canning became a Commissioner of the Board of Control for India. Canning wrote on 16 April: “Here I am immersed in papers, of which I do not yet comprehend three words in succession; but I shall get at their meaning by degrees and at my leisure. No such hard work here as at my former office. No attendance but when I like it, when there are interesting letters received from India (as is now the case) or to be sent out there”.

Paymaster of the Forces: 1800–1801

Canning was appointed Paymaster of the Forces (and therefore to the Privy Council as well) in 1800. In February 1801 Pitt resigned as Prime Minister due to the King’s opposition to Catholic Emancipation. Canning, despite Pitt’s advice to stay in office, loyally followed him into opposition. The day after Canning wrote Lady Malmesbury: “I resign because Pitt resigns. And that is all”.

Backbenches: 1801–1804

Canning disliked being out of office, and wrote on to John Hookham Frere in summer 1801: “But the thought will obtrude itself now and then that I am not where I should be – non hoc pollicitus.” He also claimed that Pitt had done “scrupulously and magnanimously right by everyone but me”. At the end of September 1801 Canning wrote to Frere, saying of Pitt: “I do love him, and reverence him as I should a Father – but a Father should not sacrifice me, with my good will. Most heartily I forgive him, But he has to answer to himself, and to the country for much mischief that he has done and much that is still to do.” Pitt wished for Canning to enter Addington’s government, a move which Canning looked on as a horrible dilemma but in the end he turned the offer down.

Canning opposed the preliminaries of the Peace of Amiens signed on 1 October. He did not vote against it due to his personal devotion to Pitt. He wrote on 22 November: “I would risk my life to be assured of being able to act always with P in a manner satisfactory to my own feelings and sense of what is right, rather than have to seek that object in separation from him.” On 27 May 1802 in the Commons Canning requested that all grants of land in Trinidad (captured by Britain from Spain) should be rejected until Parliament had decided what to do with the island. The threat that it could be populated by slaves like other West Indian islands was real. Canning instead wanted it to have a military post and that it should be settled with ex-soldiers, free blacks and creoles, with the native American population protected and helped. He also asserted that the island should be used to test the theory that better methods of cultivation in land would lessen the need for slaves. Addington conceded to Canning’s demands and the Reverend William Leigh believed Canning had saved 750,000 lives.

At a dinner to celebrate Pitt’s birthday in 1802, Canning wrote the song ‘The Pilot that Weathered the Storm’, performed by a tenor from Drury Lane, Charles Dignum:

And oh! if again the rude whirlwind should rise,

The dawnings of peace should fresh darkness deform,

The regrets of the good and the fears of the wise

Shall turn to the Pilot that weathered the Storm.

In November Canning spoke out openly in support of Pitt in the Commons. One observer thought that Canning made incomparably the best speech and that his defence of Pitt’s administration “one of the best things, either argumentatively as to matter, or critically and to manner and style” that he could ever remember. On 8 December Sheridan spoke out in defence of Addington and denied that Pitt was the only man who could save the country. Canning replied by criticising the Addington government’s foreign policy and claimed that the House should recognise the greatness of the country and Pitt, who ought to be its leader. He argued against those, such as Wilberforce, who held that Britain could safely maintain a policy of isolation: “Let us consider the state of the world as it is, not as we fancy it ought to be. Let us not seek to hide from our own eyes…the real, imminent and awful danger which threatens us.” Also, he objected to the notion that Britain could choose between greatness and happiness: “The choice is not in our power. We have…no refuge in littleness. We must maintain ourselves what we are, or cease to have a political existence worth preserving.” Furthermore, he openly declared for Pitt and said: “Away with the cant of “measures, not men”, the idle supposition that it is the harness and not the horses that draw the chariot along.” Kingdoms rise and fall due to what degree they are upheld “not by well-meaning endeavours…but by commanding, over-awing talents…retreat and withdraw as much as he will, he must not hope to efface the memory of his past services from the gratitude of his country; he cannot withdraw himself from the following of a nation; he must endure the attachment of a people whom he has saved.” In private Canning was fearful that if Pitt did not return to power, Fox would: “Sooner or later he must act or the country is gone.”

Canning approved of the declaration of war against France on 18 May 1803. Canning was angered by Pitt’s desire not to proactively work to turn out the ministry but support the ministry when it adopted sound policies. However in 1804, to Canning’s delight, Pitt began to work against the Addington government. After Pitt delivered a stinging attack on the government’s defence measures on 25 April, Canning launched his own attack on Addington, which made Addington furious. On 30 April Lord Eldon, the Lord Chancellor, asked Pitt to submit a new administration to the King.

Treasurer of the Navy: 1804–1806

Canning returned to office in 1804 with Pitt, becoming Treasurer of the Navy. In 1805 he offered Pitt his resignation after Addington was given a seat in the Cabinet. He wrote to Lady Hester to say he felt humiliated that Addington was a minister “and I am – nothing. I cannot help it, I cannot face the House of Commons or walk the streets in this state of things, as I am”. After reading this letter Pitt summoned Canning to London for a meeting, where he told him that if he resigned it would open a permanent beach between the two of them as it would cast a slur on his conduct. He offered Canning the office of Secretary of State for Ireland but he refused on the grounds that this would look like he was being got out of the way. Canning eventually decided not to resign and wrote that “I am resolved to “sink or swim” with Pitt, though he has tied himself to such sinking company. God forgive him” Canning left office with the death of Pitt; he was not offered a place in Lord Grenville’s administration.

Foreign Secretary: 1807–1809

Canning was appointed Foreign Secretary in the new government of the Duke of Portland in 1807. Given key responsibilities for the country’s diplomacy in the Napoleonic Wars, he was responsible for planning the attack on Copenhagen in September 1807, much of which he undertook at his country estate, South Hill Park at Easthampstead in Berkshire.

After the defeat of Prussia by the French, the neutrality of Denmark looked increasingly fragile. Canning was worried that Denmark might, under French pressure, become hostile to Britain. On the night of 21/22 July 1807 Canning received intelligence directly from Tilsit (where Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I of Russia were negotiating a treaty) which appeared “to rest on good authority” that Napoleon had proposed to the Tsar a great naval combination against Britain, of which Denmark and Portugal would be members.

On 30 July a military force 25,000 strong set sail for Denmark, with Francis Jackson travelling the day after. Canning instructed Jackson that his overriding aim was to secure the possession of the Danish navy by offering the Danes a treaty of alliance and mutual defence and whereby they would be given back their fleet at the end of the war. On 31 July Canning wrote to his wife: “The anxious interval between this day and the hearing the result of his [Jackson’s] expedition will be long and painful indeed. Long, I mean, in feeling. In fact it will be about a fortnight or three weeks…I think we have made success almost certain. But the measure is a bold one and if it fails – why we must be impeached I suppose – and dearest dear will have a box at the trial”. The day after he wrote that he had received a letter the previous night which provided an “account of the French being actually about to do that act of hostility, the possibility of which formed the groundwork of my Baltic plan. My fear was that the French might not be the aggressors – and then ours would have appeared a strong measure, fully justifiable I think and absolutely necessary, but without apparent necessity or justification. Now the aggression will justify us fully…I am therefore quite easy as to the morality and political wisdom of our plan”. Napoleon had on 31 July instructed his Foreign Minister, Talleyrand, to inform the Danes that if they did not wish for Holstein to be invaded and occupied by Jean Bernadotte they must prepare for war against Britain. Canning wrote to his wife on 1 August: “Now for the execution and I confess to my own love, I wake an hour or two earlier than I ought to, thinking of this execution. I could not sleep after asses’ milk today, thought I was not in bed till 1/2 p.2”. On 25 August he wrote to Granville Leveson-Gower: “The suspense is, as you may well imagine, agitating and painfil in the extreme; but I have an undiminished confidence as to the result, either by force or by treaty. The latter however is so infinitely preferable to the former that the doubt whether it has been successful is of itself almost as anxious as if the whole depended on it alone”.

On 2 September, after Jackson’s negotiations proved unsuccessful, the British fleet began bombarding Copenhagen until when on 7pm 5 September the Danes requested a truce. On 7 September the Danes agreed to hand over their navy (18 ships of the line, 15 frigates and 31 smaller ships) and naval stores and the British agreed to evacuate Zealand within six weeks. On 16 September Canning received the news with relief and excitement: “Did I not tell you we would save Plumstead from bombardment?” he wrote to Revered William Leigh. On 24 September he wrote to George Rose: “Nothing was ever more brilliant, more salutary or more effectual than the success [at Copenhagen]”. On 30 September he wrote Lord Boringdon that he hoped Copenhagen would “stun Russia into her sense again”. Canning wrote to Gower on 2 October 1807: “We are hated throughout Europe and that hate must be cured by fear”. After the news of Russia’s declaration of war against Britain reached London on 2 December, Canning wrote to Lord Boringdon two days later: “The Peace of Tilsit you see is come out. We did not want any more case for Copenhagen; but if we had, this gives it us”.

On 3 February 1808 the opposition leader George Ponsonby requested the publication of all information on the strength and battle-worthiness of the Danish fleet sent by the British envoy at Copenhagen. Canning replied with a speech nearly three hours long, described by Lord Palmerston as “so powerful that it gave a decisive turn to the debate”. Lord Grey said his speech was “eloquent and powerful” but that he had never heard such “audacious misrepresentation” and “positive falsehood”. On 2 March the opposition moved a vote of censure over Copenhagen, defeated by 224 votes to 64 after Canning gave a speech, in the words of Lord Glenbervie, so “very witty, very eloquent and very able”. In November 1807, Canning oversaw the Portuguese royal family’s flight from Portugal to Brazil.

Duel with Castlereagh

In 1809 Canning entered into a series of disputes within the government that were to become famous. He argued with the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Castlereagh, over the deployment of troops that Canning had promised would be sent to Portugal but which Castlereagh sent to the Netherlands. The government became increasingly paralysed in disputes between the two men. Portland was in deteriorating health and gave no lead, until Canning threatened resignation unless Castlereagh were removed and replaced by Lord Wellesley. Portland secretly agreed to make this change when it would be possible.

Castlereagh discovered the deal in September 1809 and challenged Canning to a duel. Canning accepted the challenge and it was fought on 21 September 1809 on Putney Heath. Canning, who had never before fired a pistol, widely missed his mark. Castlereagh, who was regarded as one of the best shots of his day, wounded his opponent in the thigh. There was much outrage that two cabinet ministers had resorted to such a method. Shortly afterwards the ailing Portland resigned as Prime Minister, and Canning offered himself to George III as a potential successor. However, the King appointed Spencer Perceval instead, and Canning left office once more. He did take consolation, though, in the fact that Castlereagh also stood down. Upon Perceval’s assassination in 1812, the new Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, offered Canning the position of Foreign Secretary once more. Canning refused, as he also wished to be Leader of the House of Commons and was reluctant to serve in any government with Castlereagh.

Ambassador to Lisbon: 1814–1816

In 1814 he became the British Ambassador to Portugal, returning the following year. He received several further offers of office from Liverpool.

President of the Board of Control: 1816–1820

In 1816 he became President of the Board of Control.

Canning resigned from office once more in 1820, in opposition to the treatment of Queen Caroline, estranged wife of the new King George IV. Canning and Caroline were close friends and may have had a brief sexual affair. This would have been regarded as unacceptable.

Backbenches: 1821–1822

On 16 March 1821 Canning spoke in favour of William Plunket’s Catholic Emancipation Bill. Liverpool wished to have Canning back in the Cabinet but the King was strongly hostile to him due to his actions over the Caroline affair. The King would only allow Canning back into the Cabinet if he did not have to deal personally with him. This required the office of Governor-General of India. After deliberating on whether to accept, Canning initially declined the offer but then accepted it. On 25 April he spoke in the Commons against Lord John Russell’s motion for parliamentary reform and a few days later Canning moved for leave to introduce a measure of Catholic Emancipation (for lifting the exclusion of Catholics from the House of Lords). This passed the Commons but was rejected by the Lords.

Foreign Secretary and Leader of the House: 1822–1827

In August 1822, Castlereagh, now Marquess of Londonderry, committed suicide. Instead of going to India, Canning succeeded him as both Foreign Secretary and Leader of the House of Commons.In his second term of office he sought to prevent South America from coming into the French sphere of influence, and in this he was successful.He also gave support to the growing campaign for the abolition of slavery. Despite personal issues with Castlereagh, he continued many of his foreign policies, such as the view that the powers of Europe (Russia, France, etc.) should not be allowed to meddle in the affairs of other states. This policy enhanced public opinion of Canning as a liberal. He also prevented the United States from opening trade with the West Indies.

Prime Minister: 1827

In 1827, Liverpool suffered a severe stroke and was to die the following year. Canning, as Liverpool’s right-hand man, was then chosen by George IV to succeed him, in preference to both the Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel.Neither man agreed to serve under Canning, and they were followed by five other members of Liverpool’s Cabinet as well as 40 junior members of the government. The Tory party was now heavily split between the “High Tories” (or “Ultras”, nicknamed after the contemporary party in France) and the moderates supporting Canning, often called “Canningites”. As a result Canning found it difficult to form a government and chose to invite a number of Whigs to join his Cabinet, including Lord Lansdowne. The government agreed not to discuss the difficult question of parliamentary reform, which Canning opposed but the Whigs supported.

However, Canning’s health by this time was in steep decline. He died on 8 August 1827, in the very same room where Charles James Fox met his own end, 21 years earlier. To this day Canning’s total period in office remains the shortest of any Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, a mere 119 days. He is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Legacy

Canning has come to be regarded as a “lost leader”, with much speculation about what his legacy could have been had he lived. His government of Tories and Whigs continued for a few months under Lord Goderich but fell apart in early 1828. It was succeeded by a government under the Duke of Wellington, which initially included some Canningites but soon became mostly “High Tory” when many of the Canningites drifted over to the Whigs. Wellington’s administration would soon go down in defeat as well. Some historians have seen the revival of the Tories from the 1830s onwards, in the form of the Conservative Party, as the overcoming of the divisions of 1827. What would have been the course of events had Canning lived is highly speculative.

Rory Muir has described Canning as “the most brilliant and colourful minister, and certainly the greatest orator in the government at a time when oratory was still politically important. He was a man of biting wit and invective, with immense confidence in his own ability, who often inspired either great friendship or deep dislike and distrust…he was a passionate, active, committed man who poured his energy into whatever he undertook. This was his strength and also his weakness…the government’s ablest minister”.

Family

Canning was married to Joan, daughter of Major General John Scott on July 8th, 1800. Joan was created Viscountess Canning, on January 28, 1828, six months after the death of George.

They had 4 children:

George Charles Canning (1801–1820), died from consumption

William Pitt Canning (1802–1828), died from drowning in Madeira, Portugal

Harriet Canning (1804–1876), married the 1st Marquess of Clanricarde

Charles Canning (later 2nd Viscount Canning and 1st Earl Canning) (1812–1862)

Ministry

04/10/1827 08/08/1827

George Canning – First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons

Lord Lyndhurst – Lord Chancellor

Lord Harrowby – Lord President of the Council

The Duke of Portland – Lord Privy Seal

William Sturges Bourne – Secretary of State for the Home Department

Lord Dudley – Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

Lord Goderich – Secretary of State for War and the Colonies and Leader of the House of Lords

William Huskisson – President of the Board of Trade and Treasurer of the Navy

Charles Williams-Wynn – President of the Board of Control

Lord Bexley – Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

Lord Palmerston – Secretary at War

Lord Lansdowne – Minister without Portfolio

Changes

- May, 1827 – Lord Carlisle, the First Commissioner of Woods and Forests, enters the Cabinet

- July, 1827 – The Duke of Portland becomes a minister without portfolio.

- Lord Carlisle succeeds him as Lord Privy Seal.

- W. S. Bourne succeeds Carlisle as First Commissioner of Woods and Forests.

- Lord Lansdowne succeeds Bourne as Home Secretary.

- George Tierney, the Master of the Mint, enters the cabinet

Read Full Post »