Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

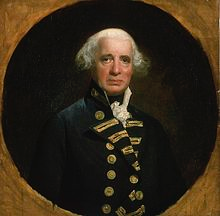

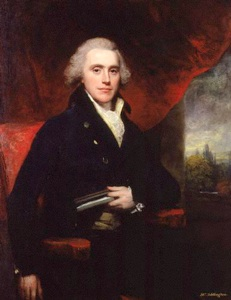

William Pitt the Younger

28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806

William Pitt

William Pitt was a British politician of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He became the youngest Prime Minister in 1783 at the age of 24. He left office in 1801, but was Prime Minister again from 1804 until his death in 1806. He was also the Chancellor of the Exchequer throughout his premiership. He is known as “the Younger” to distinguish him from his father, William Pitt the Elder, who previously served as Prime Minister of Great Britain. In 1766 he gained the style of The Honourable when his father was created the Earl of Chatham. Pitt was the second son, his brother becoming the Earl of Chatham after their father. Pitt’s brother also served in his 2nd Cabinet.

The younger Pitt’s prime ministerial tenure, which came during the reign of George III, was dominated by major events in Europe, including the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Pitt, although often referred to as a Tory, or “new Tory”, called himself an “independent Whig” and was generally opposed to the development of a strict partisan political system.

He is best known for leading Britain in the great wars against France and Napoleon. Pitt was an outstanding administrator who worked for efficiency and reform, bringing in a new generation of outstanding administrators. Regained financial stability for Britain after the American War of Independence. He raised taxes to pay for the great war against France, and cracked down on radicalism. To meet the threat of Irish support for France, he engineered the Acts of Union 1800 and tried (but failed) to get Catholic Emancipation as part of the Union. Pitt created the “new Toryism,” which revived the Tory Party and enabled it to stay in power for the next quarter-century. He defined the role of the Prime Minister as the supervisor and co-ordinator of the various Government departments.

Taking up office at the age of 24 years and 205 days, William Pitt was the youngest ever prime minister, and one of the longest in the role.

YOUTH

The son of Pitt the Elder, the Earl of Chatham, William Pitt was almost born to be prime minister. Immersed in political life from a young age, Pitt the Younger is said to have expressed parliamentary ambitions even at the age of seven. The Honourable William Pitt, second son of William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, was born at Hayes Place in the village of Hayes, Kent. Pitt was from a political family on both sides. His mother, Hester Grenville, was sister to former prime minister George Grenville. Pitt inherited brilliance and dynamism from his father’s line, and a determined, methodical nature from the Grenvilles.

Suffering from occasional poor health as a boy, he was educated at home by the Reverend Edward Wilson. An intelligent child, Pitt quickly became proficient in Latin and Greek. In 1773, aged fourteen, he attended Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he studied political philosophy, classics, mathematics, trigonometry, chemistry, and history. At Cambridge, Pitt was tutored by George Pretyman, who became a close personal friend. Pitt later appointed Pretyman Bishop of Lincoln then Winchester and drew upon his advice throughout his political career.

While at Cambridge, he befriended the young William Wilberforce, who became a lifelong friend and political ally in Parliament. Pitt tended to socialize only with fellow students and others already known to him, rarely venturing outside the university grounds. Yet he was described as charming and friendly. According to Wilberforce, Pitt had an exceptional wit along with an endearingly gentle sense of humour: “no man … ever indulged more freely or happily in that playful facetiousness which gratifies all without wounding any.”

In 1776, Pitt, plagued by poor health, took advantage of a little-used privilege available only to the sons of noblemen, and chose to graduate without having to pass examinations at the age of seventeen. Pitt’s father, who had by then been raised to the peerage as Earl of Chatham, died in 1779. As a younger son, Pitt the Younger received a small inheritance. He received legal education at Lincoln’s Inn and was called to the bar in the summer of 1780.

EARLY POLITICAL CAREER

During the general elections of September 1780, Pitt contested the University of Cambridge seat, but lost. Still intent on entering Parliament, Pitt, with the help of his university comrade, Charles Manners, 4th Duke of Rutland, secured the patronage of James Lowther. Lowther effectively controlled the pocket borough of Appleby; a by-election in that constituency sent Pitt to the House of Commons in January 1781. He was then 21. Pitt’s entry into parliament is somewhat ironic as he later railed against the very same pocket and rotten boroughs that had given him his seat.

In Parliament, the youthful Pitt cast aside his tendency to be withdrawn in public, emerging as a noted debater right from his Maiden speech. Pitt originally aligned himself with prominent Whigs such as Charles James Fox. With the Whigs, Pitt denounced the continuation of the American War of Independence, as his father strongly had. Instead he proposed that the Prime Minister, Lord North, make peace with the rebellious American colonies. Pitt also supported parliamentary reform measures, including a proposal that would have checked electoral corruption. He renewed his friendship with William Wilberforce, now MP for Hull, with whom he frequently met in the gallery of the House of Commons.

After Lord North’s ministry collapsed in 1782, the Whig Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham was appointed Prime Minister. Pitt was offered the minor post of Vice-Treasurer of Ireland; but he refused, considering the post too subordinate.

The following year Pitt became Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House under Lord Shelburne. His acceptance was regarded as a betrayal by Fox, who had refused to serve in this government himself. He was 24 when he took on the role, which caused some public concern. A popular ditty commented that it was “a sight to make all nations stand and stare: a kingdom trusted to a schoolboy’s care.”

Lord Rockingham died only three months after coming to power; he was succeeded by another Whig, William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne. Many Whigs who had formed a part of the Rockingham ministry, including Fox, now refused to serve under the new Prime Minister. Pitt, however, was comfortable joining the Shelburne Government; he was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Fox, who became Pitt’s lifelong political rival, then joined a coalition with Lord North, with whom he collaborated to bring about the defeat of the Shelburne administration. When Lord Shelburne resigned in 1783, King George III, who despised Fox, offered to appoint Pitt to the office of Prime Minister. But Pitt wisely declined, for he knew he would be incapable of securing the support of the House of Commons. The Fox-North Coalition rose to power in a Government nominally headed by William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland.

Pitt, who had been stripped of his post as Chancellor of the Exchequer, joined the Opposition. He raised the issue of parliamentary reform in order to strain the uneasy Fox-North Coalition, which included both supporters and detractors of reform. He did not advocate an expansion of the electoral franchise, but he did seek to address bribery and rotten boroughs. Though his proposal failed, many reformers in Parliament came to regard him as their leader, instead of Charles James Fox with whom he had become a fierce rival.

The Fox-North Coalition fell in December 1783, after Fox had introduced Edmund Burke’s bill to reform the East India Company to gain the patronage he so greatly lacked while the King refused to support him. Fox stated the bill was necessary to save the company from bankruptcy. Pitt responded that: “Necessity was the plea for every infringement of human freedom. It was the argument of tyrants; it was the creed of slaves.”

The King was opposed to the bill; when it passed in the House of Commons, he secured its defeat in the House of Lords by threatening to regard anyone who voted for it as his enemy. Following the bill’s failure in the Upper House, George III dismissed the coalition government and finally entrusted the premiership to William Pitt, after having offered the position to him three times previously.

A constitutional crisis arose when the king dismissed the Fox-North coalition government and named Pitt to replace it. Faced by a hostile majority in Parliament Pitt in a matter of months solidified his position. Some historians argue that his success was inevitable given the decisive importance of monarchical power; others argue that the king gambled on Pitt and that both would have failed but for a run of good fortune.

Pitt, at the age of 24, became Great Britain’s youngest Prime Minister ever and was ridiculed for his youth. A popular ditty commented that it was “a sight to make all nations stand and stare: a kingdom trusted to a schoolboy’s care”. Many saw it simply as a stop-gap appointment until some more senior statesman took on the role. However, although it was widely predicted that the new “mince-pie administration” would not last out the Christmas season, it survived for seventeen years.

So as to reduce the power of the Opposition, Pitt offered Charles James Fox and his allies posts in the Cabinet; Pitt’s refusal to include Lord North, however, thwarted his efforts. The new Government was immediately on the defensive and in January 1784 was defeated on a motion of no confidence.

Pitt, however, took the unprecedented step of refusing to resign, despite this defeat. He retained the support of the King, who would not entrust the reins of power to the Fox-North Coalition. He also received the support of the House of Lords, which passed supportive motions, and many messages of support from the country at large, in the form of petitions approving of his appointment which influenced some Members to switch their support to Pitt. At the same time, he was granted the Freedom of the City of London.

When he returned from the ceremony to mark this, men of the City pulled Pitt’s coach home themselves, as a sign of respect. When passing a Whig club, the coach came under attack from a group of men who tried to assault Pitt. When news of this spread, it was assumed Fox and his associates had tried to bring down Pitt by any means.

Pitt gained great popularity with the public at large as “Honest Billy” who was seen as a refreshing change from the dishonesty, corruption and lack of principles widely associated with both Fox and North. Despite a series of defeats in the House of Commons, Pitt defiantly remained in office, watching the Coalition’s majority shrink as some Members of Parliament left the Opposition to abstain.

In March 1784, Parliament was dissolved, and a general election ensued. An electoral defeat for the Government was out of the question because Pitt enjoyed the support of King George III. Patronage and bribes paid by the Treasury were normally expected to be enough to secure the Government a comfortable majority in the House of Commons but on this occasion the government reaped much popular support as well. In most popular constituencies, the election was fought between candidates clearly representing either Pitt or Fox and North. Early returns showed a massive swing to Pitt with the result that many Opposition Members who still hadn’t faced election either defected, stood down, or made deals with their opponents to avoid expensive defeats.

A notable exception came in Fox’s own constituency of Westminster which contained one of the largest electorates in the country. In a contest estimated to have cost a quarter of the total spending in the entire country, Fox bitterly fought against two Pittite candidates to secure one of the two seats for the constituency. Great legal wranglings ensued, including the examination of every single vote cast, which dragged on for more than a year. Meanwhile, Fox sat for the pocket borough of Tain Burghs. Many saw the dragging out of the result as being unduly vindictive on the part of Pitt and eventually the examinations were abandoned with Fox declared elected. Elsewhere Pitt won a personal triumph when he was elected a Member for the University of Cambridge, a constituency he had long coveted and which he would continue to represent for the remainder of his life.

IMPACT OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

Losing the war and the 13 colonies was a shock to the British system. The war revealed the limitations of Britain’s fiscal-military state when it had powerful enemies, no allies, depended on extended and vulnerable transatlantic lines of communication, and was faced for the first time since the 17th century by both Protestant and Catholic foes.

The defeat heightened dissension and escalated political antagonism to the King’s ministers. Inside parliament, the primary concern changed from fears of an over-mighty monarch to the issues of representation, parliamentary reform, and government retrenchment. Reformers sought to destroy what they saw as widespread institutional corruption. The result was a crisis from 1776-1783. The peace in 1783 left France financially prostrate, while the British economy boomed thanks to the return of American business.

That crisis ended in 1784 thanks to the King’s shrewdness in outwitting Fox and renewed confidence in the system engendered by the leadership of Pitt. Historians conclude that loss of the American colonies enabled Britain to deal with the French Revolution with more unity and organization than would otherwise have been the case.

THE FIRST MINISTRY

Against early predictions, Pitt’s ministry survived for 17 years. In government, he stood for parliamentary reform to reduce the direct influence of the monarch and the capacity for bribery; union with Ireland; Catholic emancipation; reorganization of the East India Company; reduction of the national debt; and free trade.

During his first year he suffered many defeats but was undeterred, and was increasingly fired by criticisms from his rival, Fox. His popularity rose steadily, and he won a very large majority in a well-timed General Election in 1784. During 1784 Pitt set about reducing the national debt and combating smuggling.

His administration secure, Pitt could begin to enact his agenda. His first major piece of legislation as Prime Minister was the India Act 1784, which re-organized the British East India Company and kept a watch over corruption. The India Act created a new Board of Control to oversee the affairs of the East India Company. It differed from Fox’s failed India Bill 1783 and specified that the Board would be appointed by the King.

Pitt was appointed, along with Lord Sydney who was appointed President. The Act centralized British rule in India by reducing the power of the Governors of Bombay and Madras and by increasing that of the Governor-General, Charles Cornwallis. Further augmentations and clarifications of the Governor-General’s authority were made in 1786, presumably by Lord Sydney, and presumably as a result of the Company’s setting up of Penang with their own Superintended (Governor), Captain Francis Light, in 1786.

In domestic politics, Pitt also concerned himself with the cause of parliamentary reform. The session of 1785 was more difficult. Pitt launched a Reform Bill, which would rationalize dozens of “rotten borough” constituencies. This key bill was rejected, as was a Union with Ireland Bill. In 1785, he introduced a bill to remove the representation of thirty-six rotten boroughs, and to extend in a small way, the electoral franchise to more individuals. Pitt’s support for the bill, however, was not strong enough to prevent its defeat in the House of Commons. The bill introduced in 1785 was Pitt’s last parliamentary reform proposal introduced in Parliament.

Another important domestic issue with which Pitt had to concern himself was the national debt, which had increased dramatically due to the rebellion of the American colonies. Pitt sought to eliminate the national debt by imposing new taxes. Pitt also introduced measures to reduce smuggling and fraud. In 1786, he instituted a sinking fund to reduce the national debt. Each year, £1,000,000 of the surplus revenue raised by new taxes was to be added to the fund so that it could accumulate interest; eventually, the money in the fund was to be used to pay off the national debt. The system was extended in 1792 so as to take into account any new loans taken by the government.

Pitt sought European alliances to restrict French influence, forming the Triple Alliance with Prussia and the United Provinces in 1788. During the Nootka Sound Controversy in 1790, Pitt took advantage of the alliance to force Spain to give up its claim to exclusive control over the western coast of North and South America. The Alliance, however, failed to produce any other important benefits for Great Britain.

In 1788, Pitt faced a major crisis when the King fell victim to a mysterious illness, a form of mental disorder that incapacitated him. (The Madness) If the sovereign was incapable of fulfilling his constitutional duties, Parliament would need to appoint a regent to rule in his place. All factions agreed the only viable candidate was the king’s eldest son, HRH The Prince George, Prince of Wales. The Prince, however, was a supporter of Charles James Fox; had he come to power, he would almost surely have dismissed Pitt. However, he did not have such an opportunity, as Parliament spent months debating legal technicalities relating to the Regency. Fortunately for Pitt, the king recovered in February 1789, just after a Regency Bill had been introduced and passed in the House of Commons.

The general elections of 1790 resulted in a majority for the government, and Pitt continued as Prime Minister. In 1791, he proceeded to address one of the problems facing the growing British Empire: the future of British Canada. By the Constitutional Act of 1791, the province of Quebec was divided into two separate provinces: the predominantly French Lower Canada and the predominantly English Upper Canada. In August 1792, George III appointed Pitt to the honorary post of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. The King had in 1791 offered him a Knighthood of the Garter, but he suggested the honour go to his elder brother, the second Earl of Chatham.

In the early 1790s the development of the revolution in France caused Pitt to worry about its effects in Britain. He reacted by expelling the French ambassador, and was blamed by Fox for the war with France that began in 1793.

The French Revolution encouraged many in Great Britain to once again speak of parliamentary reform, an issue which had not been at the political forefront since Pitt’s reform bill was defeated in 1785. The reformers, however, were quickly labelled as radicals and as associates of the French revolutionaries. Subsequently, in 1794 Pitt’s administration tried three of them for treason but lost. Parliament began to enact repressive legislation in order to silence the reformers. Individuals who published seditious material were punished, and, in 1794, the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus was suspended. Other repressive measures included the Seditious Meetings Act (which restricted the right of individuals to assemble publicly) and the Combination Acts (which restricted the formation of societies or organisations that favoured political reforms). Problems manning the Royal Navy also led to Pitt to introduce the Quota System in 1795 addition to the existing system of Impressment.

The war with France was extremely expensive, straining Great Britain’s finances. Unlike the latter stages of the Napoleonic Wars, at this point Britain had only a very small standing army, and thus contributed to the war effort mainly by sea power and by supplying funds to other coalition members facing France. In 1797, Pitt was forced to protect the kingdom’s gold reserves by preventing individuals from exchanging banknotes for gold. Great Britain would continue to use paper money for over two decades. Pitt was also forced to introduce Great Britain’s first ever income tax. The new tax helped offset losses in indirect tax revenue, which had been caused by a decline in trade. Despite the efforts of Pitt and the British allies, the French continued to defeat the members of the First Coalition, which collapsed in 1798. A Second Coalition, consisting of Great Britain, Austria, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire, was formed, but it, too, failed to overcome the French. The fall of the Second Coalition with the defeat of the Austrians at Marengo (14 June 1800) left Great Britain facing France alone.

The French Revolution revived religious and political problems in Ireland, a realm under the rule of the King of Great Britain. In 1798, Irish nationalists even attempted a rebellion, believing that the French would help them overthrow the monarchy. Pitt firmly believed that the only solution to the problem was a union of Great Britain and Ireland. Following the defeat of the rebellion which was assisted by France, he advanced this policy. The union was established by the Act of Union 1800; compensation and patronage ensured the support of the Irish Parliament. Great Britain and Ireland were formally united into a single realm, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, on 1 January 1801.

Pitt sought to inaugurate the new kingdom by granting concessions to Roman Catholics, who formed a majority in Ireland, by abolishing various political restrictions under which they suffered. George III, however, did not share the same view. The King was strongly opposed to Catholic Emancipation; he argued that to grant additional liberty would violate his coronation oath, in which he had promised to protect the established Church of England. Pitt, unable to change the King’s strong views, resigned on 16 February 1801, so as to allow Henry Addington, his political friend, to form a new administration. At about the same time, however, the King suffered a renewed bout of madness; thus, Addington could not receive his formal appointment. Though he had resigned, Pitt temporarily continued to discharge his duties; on 18 February 1801, he brought forward the annual budget. Power was transferred from Pitt to Addington on 14 March, when the King recovered.

Pitt supported the new administration, but with little enthusiasm; he frequently absented himself from Parliament, preferring to remain in his Lord Warden’s residence of Walmer Castle – before 1802 usually spending an annual late-summer holiday there, and later often present from the spring until the autumn.

From the castle, he helped organize a local volunteer force in anticipation of a French invasion, acted as colonel of a battalion raised by Trinity House – he was also a Master of Trinity House – and encouraged the construction of Martello towers and the Royal Military Canal in Romney Marsh. He rented land abutting the Castle to farm, and on which to lay out trees and walks. His niece Lady Hester Stanhope designed and managed the gardens and acted as his hostess.

After France had forced peace and recognition of the French Republic from the Russian Empire in 1799 and from the Holy Roman Emperor (Austria) in 1801, the Treaty of Amiens between France and Britain marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars. By 1803, however, war had broken out again between Britain and the new First French Empire under Napoleon. Although Addington had previously invited him to join the Cabinet, Pitt preferred to join the Opposition, becoming increasingly critical of the government’s policies. Addington, unable to face the combined opposition of Pitt and Fox, saw his majority gradually evaporate. By the end of April 1804, Addington, who had lost his parliamentary support, had decided to resign.

Three years after leaving office, King George III asked Pitt to form a second government when Napoleon was threatening invasion. Pitt accepted, despite his failing health, possible alcoholism and limited support in the House of Commons.

SECOND MINISTRY

Pitt returned to the premiership on 10 May 1804. He had originally planned to form a broad coalition government, but faced the opposition of George III to the inclusion of Fox. Moreover, many of Pitt’s former supporters, including the allies of Addington, joined the Opposition. Thus, Pitt’s Second Ministry was considerably weaker than his first.

The British Government began placing pressure on the French Emperor, Napoleon I. Thanks to Pitt’s efforts, Britain joined the Third Coalition, an alliance that also involved Austria, Russia, and Sweden. In October 1805, the British Admiral, Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, won a crushing victory in the Battle of Trafalgar, ensuring British naval supremacy for the remainder of the war.

At the annual Lord Mayor’s Banquet toasting him as “the Saviour of Europe”, Pitt responded that, “I return you many thanks for the honour you have done me; but Europe is not to be saved by any single man. England has saved herself by her exertions, and will, as I trust, save Europe by her example.”

Nevertheless, the Coalition collapsed, having suffered significant defeats at the Battle of Ulm (October 1805) and the Battle of Austerlitz (December 1805). After hearing the news of Austerlitz Pitt referred to a map of Europe, “Roll up that map; it will not be wanted these ten years.”

DEATH

The setbacks took a toll on Pitt’s health. He had long suffered from poor health, beginning in childhood, and was plagued with gout and “biliousness” worsened by a fondness for port that began when he was advised to drink the wine to deal with his chronic ill-health. On 23 January 1806, Pitt died, probably from peptic ulceration of his stomach or duodenum; he was unmarried and left no children. He died at the age of 46. His last words were ‘Oh my country! How I love my country!’

Pitt’s debts amounted to £40,000 when he died, but Parliament agreed to pay them on his behalf. A motion was made to honour him with a public funeral and a monument; it passed despite the opposition of Fox. Pitt’s body was buried in Westminster Abbey on 22 February, having lain in state for two days in the Palace of Westminster. Pitt was succeeded as Prime Minister by William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville, who headed the Ministry of All the Talents, a coalition which included Charles James Fox.

William Pitt the Younger was a powerful Prime Minister who consolidated the powers of his office. Though he was sometimes opposed by members of his Cabinet, he helped define the role of the Prime Minister as the supervisor and co-ordinator of the various Government departments. He was not, however, the supreme political influence in the nation, for the King remained the dominant force in Government. Pitt was Prime Minister not because he enjoyed the support of the electorate or of the House of Commons, but because he retained the favour of the Crown.

One of Pitt’s most important accomplishments was a rehabilitation of the nation’s finances after the American War of Independence. Pitt helped the Government manage the mounting national debt, and made changes to the tax system in order to improve its efficiency.

Some of Pitt’s other domestic plans were not as successful; he failed to secure parliamentary reform, emancipation, or the abolition of the slave trade – although this last did take place with the Slave Trade Act 1807, the year after his death.

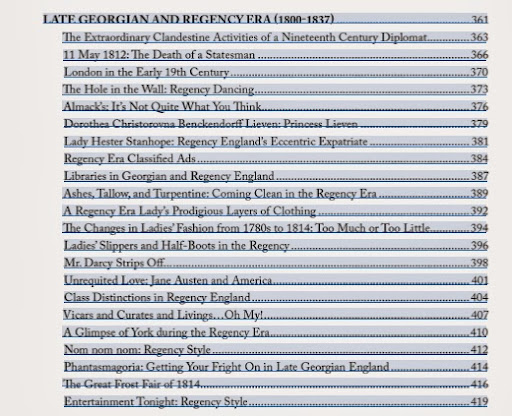

First Ministry

12/19/1783 03/14/1801

Office Name Term

First Lord of the Treasury

Chancellor of the Exchequer William Pitt 1783-1801

Lord Chancellor The Lord Thurlow 1783-1792

Lord President of the Council The Earl Gower 1783-1784

Lord Privy Seal The Duke of Rutland 1783-1784

Foreign Secretary The Marquess of Carmarthen 1783-1791

Home Secretary The Lord Sydney 1783-1789

First Lord of the Admiralty The Viscount of Howe 1783-1788

Master-General of the Ordnance The Duke of Richmond 1784-1795

Changes

- March, 1784 – The Duke of Rutland becomes Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, remaining also Lord Privy Seal.

- December, 1784 – Lord Gower (Lord Stafford from 1786) succeeds the Duke of Rutland as Lord Privy Seal (Rutland remains Viceroy of Ireland). Lord Camden succeeds Gower as Lord President.

- November, 1787 – Lord Buckingham succeeds the Duke of Rutland as Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland

- July, 1788 – Lord Chatham, Pitt’s elder brother, succeeds Lord Howe as First Lord of the Admiralty

- June, 1789 – William Wyndham Grenville (Lord Grenville from 1790), succeeds Lord Sydney as Home Secretary.

- October, 1789 – Lord Westmorland succeeds Lord Buckingham as Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland

- June, 1791 – Lord Grenville succeeds the Duke of Leeds (Lord Carmarthen before 1789) as Foreign Secretary. Henry Dundas succeeds Grenville as Home Secretary. Lord Hawkesbury (from 1796 the Earl of Liverpool), the President of the Board of Trade, joins the Cabinet.

- June, 1792 – Lord Thurlow resigns as Lord Chancellor. The Great Seal goes into commission.

- January, 1793 – Lord Loughborough becomes Lord Chancellor

- July, 1794 – Lord Fitzwilliam succeeds Lord Camden as Lord President. Henry Dundas takes the new Secretaryship of State for War, while the Duke of Portland succeeds Dundas as Home Secretary. Lord Spencer succeeds Stafford as Lord Privy Seal. William Windham enters the Cabinet as Secretary at War.

- December, 1794 – Lord Chatham succeeds Spencer as Lord Privy Seal. Lord Spencer succeeds Chatham as First Lord of the Admiralty. Lord Fitzwilliam succeeds Lord Westmorland as Viceroy of Ireland. Lord Mansfield succeeds Fitzwilliam as Lord President.

- February, 1795 – Lord Cornwallis succeeds the Duke of Richmond as Master-General of the Ordnance.

- March, 1795 – Lord Camden succeeds Lord Fitzwilliam as Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland.

- September, 1796 – Lord Chatham succeeds Lord Mansfield as Lord President, remaining also Lord Privy Seal.

- February, 1798 – Lord Westmorland succeeds Lord Chatham as Lord Privy Seal. Chatham remains Lord President.

- June, 1798 – Lord Cornwallis succeeds Lord Camden as Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, remaining also Master-General of the Ordnance.

- February, 1801 – Lord Grenville, Lord Spencer, and William Windham resign from the Cabinet. The first two are succeeded by Lord Hawkesbury and Lord St Vincent, while Windham’s successor is not in cabinet.

Second Ministry

05/10/1804 01/23/1806

Name Office Term

First Lord of the Treasury

Chancellor of the Exchequer William Pitt 1804-1806

Lord Chancellor The Lord Eldon 1804-1806

Lord President of the Council The Duke of Portland 1804–1805

Lord Privy Sea The Earl of Westmorland 1804-1806

Foreign Secretary The Lord Harrowby 1804–1805

Home Secretary The Lord Hawkesbury 1804-1806

War and Colonial Secretary The Earl Camden 1804–1805

First Lord of the Admiralty The Viscount Melville 1804–1805

Master-General of the Ordnance The Earl of Chatham 1804-1806

President of the Board of Trade The Duke of Montrose 1804-1806

President of the Board of Control Viscount Castlereagh 1804-1806

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster The Lord Mulgrave 1804–1805

Changes

- January, 1805 – Lord Mulgrave succeeds Lord Harrowby as Foreign Secretary. Lord Buckinghamshire (previously Lord Hobart) succeeds Mulgrave at the Duchy of Lancaster. Lord Sidmouth succeeds the Duke of Portland as Lord President. Portland becomes a Minister without Portfolio.

- April, 1805 – Lord Barham succeeds Lord Melville as First Lord of the Admiralty

- July, 1805 – Lord Harrowby succeeds Lord Buckinghamshire as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Lord Camden succeeds Lord Sidmouth as Lord President. Lord Castlereagh succeeds Camden as Colonial Secretary, remaining also at the Board of Control.

Read Full Post »

The End of the World,

The End of the World, The Shattered Mirror

The Shattered Mirror Two Peas in a Pod

Two Peas in a Pod Beggars Can’t Be Choosier

Beggars Can’t Be Choosier Colonel Fitzwilliam’s Correspondence

Colonel Fitzwilliam’s Correspondence Jane Austen and Ghosts

Jane Austen and Ghosts

The Prisoner of Zenda.

The Prisoner of Zenda.