Regency Personalities Series

In my attempts to provide us with the details of the Regency, today I continue with one of the many period notables.

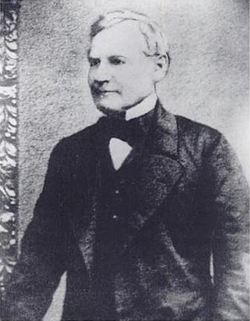

Sir Charles Elliot

15 August 1801 – 9 September 1875

Charles Elliot

Sir Charles Elliot was born in Dresden, Saxony, on 15 August 1801 to Margaret and Hugh Elliot. He was one of nine children. His uncle was Scottish diplomat Gilbert Elliott, 1st Earl of Minto, and Gilbert Elliott, 2nd Earl of Minto and George Eden were cousins. He was educated in Reading, Berkshire, England. On 26 March 1815, Elliot joined the Royal Navy as a first-class volunteer on board HMS Leviathan, which served in the Mediterranean Station. In July 1816, he became a midshipman on board HMS Minden, in which he served in the bombardment of Algiers against Barbary pirates in August 1816. He then served in the East Indies Station for four years under Sir Richard King. In 1820, he joined the cutter Starling under Lieutenant-Commander John Reeve in the Home Station, and HMS Queen Charlotte under James Whitshed.

In 1821, Elliot joined HMS Iphigenia under Sir Robert Mends in the West Africa Squadron. On 11 June 1822, he became a lieutenant while serving in HMS Myrmidon under Captain Henry John Leeke. He again served in the Iphigenia on 19 June, and in HMS Hussar under Captain George Harris in the West Indies Station. There, he was appointed to the schooners Union on 19 June 1825 and Renegade on 30 August. On 1 January 1826, he was nominated acting-commander of the convalescentship Serapis in Port Royal, Jamaica, where on 14 April, he served in the hospital ship Magnificent. After further employment on board HMS Bustard and HMS Harlequin, he was promoted to captain on 28 August 1828.

After retiring from active military service, Elliot followed a career in the Foreign Office. In 1830, the Colonial Office sent Elliot to Demerara in British Guiana to be Protector of Slaves and a member of the Court of Policy from 1830 to 1833. He was brought home to advise the government of administrative problems relating to the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. In a letter to the Treasury in 1833, Prime Minister Lord Howick wrote:

Lord Goderich [Secretary of State for the Colonies] feels himself bound to acknowledge that His Majesty’s Government are indebted to him [Elliot], not only for a zealous and efficient execution of the duties of his office, but for communications of peculiar value and importance sent from the Colony during the last twelve months, and for essential services rendered at a critical period since his arrival in this country … Elliot has contributed far beyond what the functions of his particular office required of him.

In late 1833, Elliot was appointed as Master Attendant to the staff of Lord Napier, Chief Superintendent of British Trade. His position was involved with British ships and crews operating between Macao and Canton. He was appointed Secretary in October 1834, Third Superintendent in January 1835, and Second Superintendent in April 1835. In 1836, he became Plenipotentiary and replaced Sir George Robinson as Chief Superintendent of British Trade. Elliot wrote to Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston in December 1839, “No man entertains a deeper detestation of the disgrace and sin of this forced traffic on the coast of China. I have steadily discountenanced it by all the lawful means in my power, and at the total sacrifice of my private comfort in the society in which I have lived for some years past.”

During the First Anglo-Chinese War, he was on board the Nemesis during most of the battles. In January 1841, he negotiated terms with Chinese Imperial Commissioner Qishan in the Convention of Chuenpi. Elliot declared, among other terms, the cession of Hong Kong Island to the United Kingdom. However, Palmerston recalled Elliot and, accusing him of disobedience and treating his instructions as “waste paper”, dismissed him. Henry Pottinger was appointed to replace him as plenipotentiary in May 1841. On 29 July, HMS Phlegeton arrived in Hong Kong with dispatches informing Elliot of the news. His administration ended on 10 August. On 24 August, he left Macao, with his family for England. As he embarked on the Atlanta, a Portuguese fort fired a thirteen gun salute.

Historian George Endacott wrote, “Elliot’s policy of conciliation, leniency, and moderate war aims was unpopular all round, and aroused some resentment among the naval and military officers of the expedition.” Responding to the accusation that “It has been particularly objected to me that I have cared too much for the Chinese”, Elliot wrote to Foreign Secretary Lord Aberdeen on 25 June 1842:

But I submit that it has been caring more for lasting British honour and substantial British interests, to protect friendly and helpful people, and to return the confidence of the great trading population of the Southern Provinces, with which it is our chief purpose to cultivate more intimate, social and commercial relations.

On 23 August 1842, Elliot arrived in the Republic of Texas, where he was chargé d’affaires and consul general until 1846. He served as Governor of Bermuda (1846–54), Governor of Trinidad (1854–56), and Governor of Saint Helena (1863–69). In the retired list, he was promoted to rear-admiral on 2 May 1855, vice-admiral on 15 January 1862, and admiral on 12 September 1865.

In Sir Henry Taylor’s play, Edwin the Fair (1842), the character Earl Athulf was based on Elliot. Taylor also mentioned Elliot in his poem, “Heroism in the Shade” (1845). Elliot was made Knight Commander of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath in 1856. He died in retirement at Withycombe Raleigh, Exmouth, Devon, England, on 9 September 1875. He is buried in the churchyard of St John-in-the-Wilderness, Exmouth. The weathered headstone inscription to his grave reads in worn lead lettering “To the memory of/Adm Sir Charles Elliot KCB/Born 15th August 1801/Died 9th September 1875/The souls of the righteous are in the hands of God”. This is the only known memorial to him anywhere in the world.

During Elliot’s naval service in the West Indies, he met Clara Genevieve Windsor (1806–1885) in Haiti, where she was born and raised. After marrying in 1828, they had two daughters and three sons:

- Harriet Agnes Elliot (1829–1896); married Edward Russell, 23rd Baron de Clifford, in 1853; four children.

- Hugh Hislop Elliot (1831–1861); Captain 1st Bombay Light Cavalry; married Louise Sidonie Perrin on 15 March 1860 in Byculla, Bombay; no known children; died at sea and memorialised in St James Cathedral, St Helena.

- Gilbert Wray Elliot (1833–1910); Bombay Civil Service; married three times, one child to each marriage; studied at Haileybury; weightlifter Launceston Elliot was his son by his third marriage.

- Frederick Eden Elliot (1837–1916); Bengal Civil Service; married in 1861; four children.

- Emma Clara Elliot (1842–1865); married George Barrow Pennell in 1864 in St Helena, where her father was governor; one child. She died in St Helena where she is memorialised in St James Cathedral.

Elliot’s wife accompanied him to Guiana from 1830 to 1833, and to China from 1834 to 1841 as well as to all of his subsequent postings around the world. After ten years of widowhood, she died on 17 October 1885 aged 80 years at the home of her husband’s nephew Capt (RN retired) Hugh Maximilian Elliot, The Bury, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire. She is buried at the Heath Lane Cemetery, Hemel Hempstead where a stone cross bears a worn inscription to her memory.